Beti and I first shared our story at ZEG Tbilisi Storytelling Festival in June. The excerpt below is the beginning of our journey as mother and daughter as originally published in Stranger’s Guide. Our full story—of building a family, finding belonging, and feeling home—is the focus of my second memoir, coming soon.

Monique:

My father, Pappi, never tired of saying, “If you don’t know where you are going, remember where you came from.”

I come from Liberia — but my life has taken me all over the world. and I’ve often felt like an outsider and had to hold on to Pappi’s words. Whether it was during American Thanksgiving, “Juletid” in Sweden, or “Las Posadas” festivities in Mexico, my thoughts inevitably turn to where I came from — Liberia.

Beti:

Growing up, I called my dad Mekalmu. Where I come from it’s normal to call your parents by their first names. I come from the Omo Valley region of Southern Ethiopia, in a village called Geza, a village so tiny, so poor and nondescript, that if you try to find it on a map you won’t.

I grew up on a farm tended by my father. Every day after breakfast, he would go out into the fields to tend his crops – wheat, barley, teff, beans, taro. He used cows for plowing because we did not have modern equipment. On very special occasions, like on the Ethiopian New Year, Enkutatash, we would kill one of the cows to eat it.

M:

At home, Pappi was always the first to wake up. At five a.m. he headed straight to the kitchen, where at least twelve chickens had been thawing overnight on the counter. He owned a restaurant named after me, called Monique’s Snack bar and restaurant — but everyone called it Maddy’s. It served the Swedish miners that came to Liberia to mine the rich seams of iron ore beneath the ground where I grew up.

I’d often find Pappi busy taking orders behind the counter. If someone wanted an ice cream, I’d race to pull a cone from the holder and pump the soft ice cream into the cone. I’d collect payment, make change, and race back to rejoin Pappi. It was a great partnership.

B:

During the summer and the school holidays, we work in the field with Melkamu, helping to plant the rows of seeds. This was very special for me, because most of the time only the boys are allowed to plough. My dad made an exception for my sisters and me.

M:

I was Pappi’s only daughter and he was determined to make me strong enough to succeed and fend for myself without being dependent on anyone, least of all a man, in a male-dominated culture. Pappi was a well- respected and prominent leader in the community, a big shot.

B:

Everyone loved my dad — he was very popular because of his good nature. When my siblings and I would go to the Jinka market on Saturdays, people would see us and ask, “Are you Melkamu’s children?” It made us all feel very proud and important to be his children.

M:

“I may not have any money to leave you when I am gone, but with your education, you can be whatever you want to be. You will always have your education, and the freedom to pursue a new passion,” my Pappi used to say.

Monique’s snack bar did so well, it ended up funding my education. My parents were able to send me away from Liberia, to boarding school in England. My memories of leaving Liberia are both vivid and bittersweet.

After boarding school, I went to university, and business school, and lived all over the world, founding my own tech company. I ended up in Mexico City, but I found myself constantly drawn back to the continent of my birth. It was as if, subconsciously, I was perennially searching for the missing piece of myself that would make me whole.

Three decades after leaving Liberia, I was sitting in my office, in Mexico City, when my life changed forever. I did not know it then, of course. It all started when my legal counsel, Ricardo, called my office. “Hola, Moneeeeeeek!” he said, in Spanish-accented English. “Guess what…we’re going to Africa!” he pronounced triumphantly. “I need your advice, my friend.”

Many people refer to Africa exactly as Ricardo had: as a single, united, homogenous country, rather than a collection of fifty-four independent nation-states, each as different from the other as Japan is from Thailand or Mexico from Brazil. Since I was the only African friend he had in Mexico—possibly the only African friend he had, period—it made perfect sense that he’d turn to me for advice. “That’s great,” I said. What part of Africa? Kenya? Tanzania? South Africa?”

“We are going to Ethiopia! The whole family!” He said.

I was confused. “Wait, what? To Ethiopia?”

“Yes. We are going to see the Mursis!”

I suggested they might be happier going on a luxury Safari in somewhere like Tanzania, or Kenya, to see big game, wildebeests, flamingos.

“You are missing the entire point, Monique,” Ricardo says cooly. “We are going to Ethiopia to experience the real Africa. The people — not the animals.”

B:

Everyone in the village is always excited when the tourists come. If we are lucky they will give us t-shirts, candy, and a little cash if we let them take our pictures. They don’t usually stay too long in Geza- most of the time they don’t even stop because our clothes are like their clothes, we don’t paint our faces, and we don’t walk around naked. They prefer to visit and take pictures of people like the Mursis, with their painted faces, their lip plates, and their body scars.

One day, we hear the tourists coming in their big white jeeps. Some of us run towards the car and start showing them examples of our pottery. By the time the tourists get out of their jeeps, walk over to our compound accompanied by their very watchful Ethiopian drivers and tour guides. We sing songs in Aari, so that their videos will have a soundtrack.

The tourists stop and get out to talk to us. They ask if they can touch our skin, as if they are at a petting zoo. Then they take our pictures and give 15 birr to each of us. I feel like the richest person in Geza.

We never see the pictures that the tourists take of us and we don’t know what they do with them because once they get back into their jeeps and drive away, we never see them again.

M:

When Ricardo returned from their trip a few months later, he invited me to his home for dinner. It was amazing, Monique,” Ricardo said. “The people, the cultures, the landscapes, all so beautiful!” He gave me a USB drive containing hundreds of pictures they’d taken on the trip.

Back home, I inserted the drive into my computer, rapidly clicking through the images. There they were —scenes of intense natural and physical beauty of land and people. A wave of nostalgia washed over me, a longing for Africa that I could almost taste on my tongue. A part of me wanted to immerse myself in these images for hours, but I resisted the urge to wade deeper into the longing, out of fear it might grow more intense and even overwhelm me. I file Ricardo’s images in a Dropbox folder, promising myself that when I was ready, I’d return to them.

B:

A year has passed and I am now seven. My dad, Melkamu, has just built a new house — the blue house, we called it — for the family, and we are all moved in. Our parents have sent us to a new government school and I am now in the second grade.

One night, about two months after school started, Melkamu woke up very sick. His stomach is hurting and he can’t bear the pain. We try to find him a ride to the hospital and can’t find one. My uncles take my dad by foot on a wooden stretcher 10 Kilometers to the nearest hospital. We are all awake and very worried. I see fear in my mother, Dami’s, eyes.

On the way to school, all I can think about is Melkamu, and if I should turn back. But I know he will be upset with me if I go back.

Three days later, at 5:00 am there was a knock at the window. I see my two uncles crying very loudly. “Melkamu is dead. He died in the hospital,” one of them says.

I collapse to the ground, banging my head on the mud floor. My world has fallen apart. Melkamu, the foundation of our family, our protector, who has given us everything, and who taught me how to farm and who let me take care of the cow, and who said that one day I will go to America, is gone. We are all alone.

M:

It was not until 2014, almost three years to the day since Ricardo sent me those photos from Ethiopia, that I resurrected this trove of Ricardo’s images from their digital tomb.

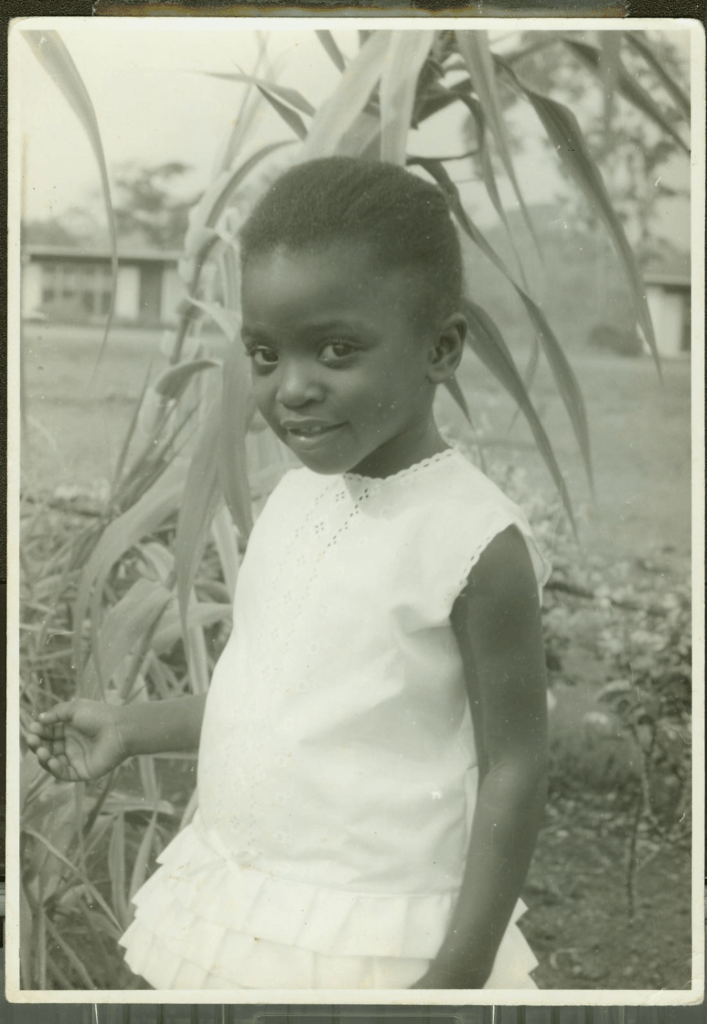

I had finally come around to “branding” my office space. Like an archeologist, I excavated a dozen or so photographs from the treasure trove to enlarge and frame for display in my office.They included an adolescent Mursi striking an Adonis-like pose,; a group of younger Mursi boys whose bodies were painted in white geometric shapes and several Hamer women from with bangs and thick plaits. There was also a photo of a group of children playing along a narrow dirt road.

My eyes kept drifting back to one particular girl in the photo. She couldn’t have been more than five, possibly six years old, and had a smile that radiated at both innocence and mischief. She was utterly her own person. And at the same time, uncannily, she looked as though she could have been the sister I never had. After blowing the photograph up, I hung it on the wall, so that the first thing I saw every morning when I walked into my office was “the girl with the smile.” She drew me to the Africa of my childhood. In her eyes, her face, her smile, I saw my father, Pappi, who had passed away more than a quarter of a century earlier.

People had always said how much I looked like him, but this little girl was his spitting image.

The story of the girl with the smile continues in my forthcoming memoir.